Every summer, as twilight falls over Japanese towns and countryside, streets light up with glowing lanterns, taiko drums echo through the air, and families gather in quiet reverence. This is Obon, one of Japan’s most deeply spiritual festivals — a time when the living welcome the spirits of the dead back home.

What is Obon?

Obon, also known as Urabon or just Bon, is a Buddhist tradition observed in mid-July or August, depending on the region. It honors the spirits of ancestors who are believed to return to the world of the living during this period. The festival blends Buddhist teachings with Japanese folk customs, creating a unique fusion of ritual, remembrance, and joy.

More than a religious holiday, Obon is a cultural homecoming. People travel back to their ancestral villages, clean family graves, offer prayers, and celebrate life through communal activities like food, music, and traditional dance.

Welcoming the Spirits

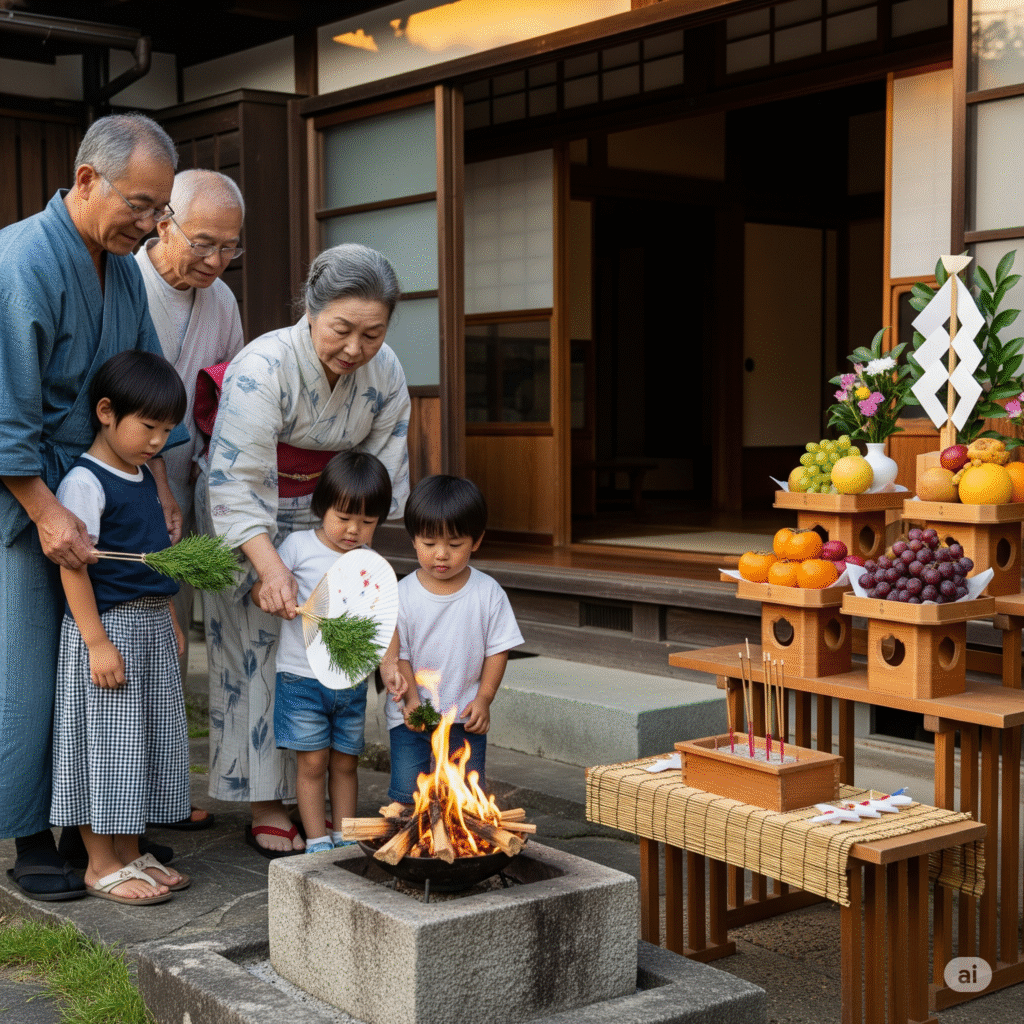

Obon typically begins with mukaebi — “welcoming fires.” Small fires or lanterns are lit outside homes to guide ancestral spirits back. Families may place offerings of food, incense, and flowers at home altars or Buddhist temples to honor their ancestors.

Altars, called butsudan, are decorated with ihai (ancestral tablets), seasonal fruits, and symbolic lotus flowers. Many households also display cucumbers and eggplants made into animals — a cucumber horse for fast arrival, and an eggplant cow for a slow return, both ensuring safe travel for the spirits.

Bon Odori: Dancing with the Past

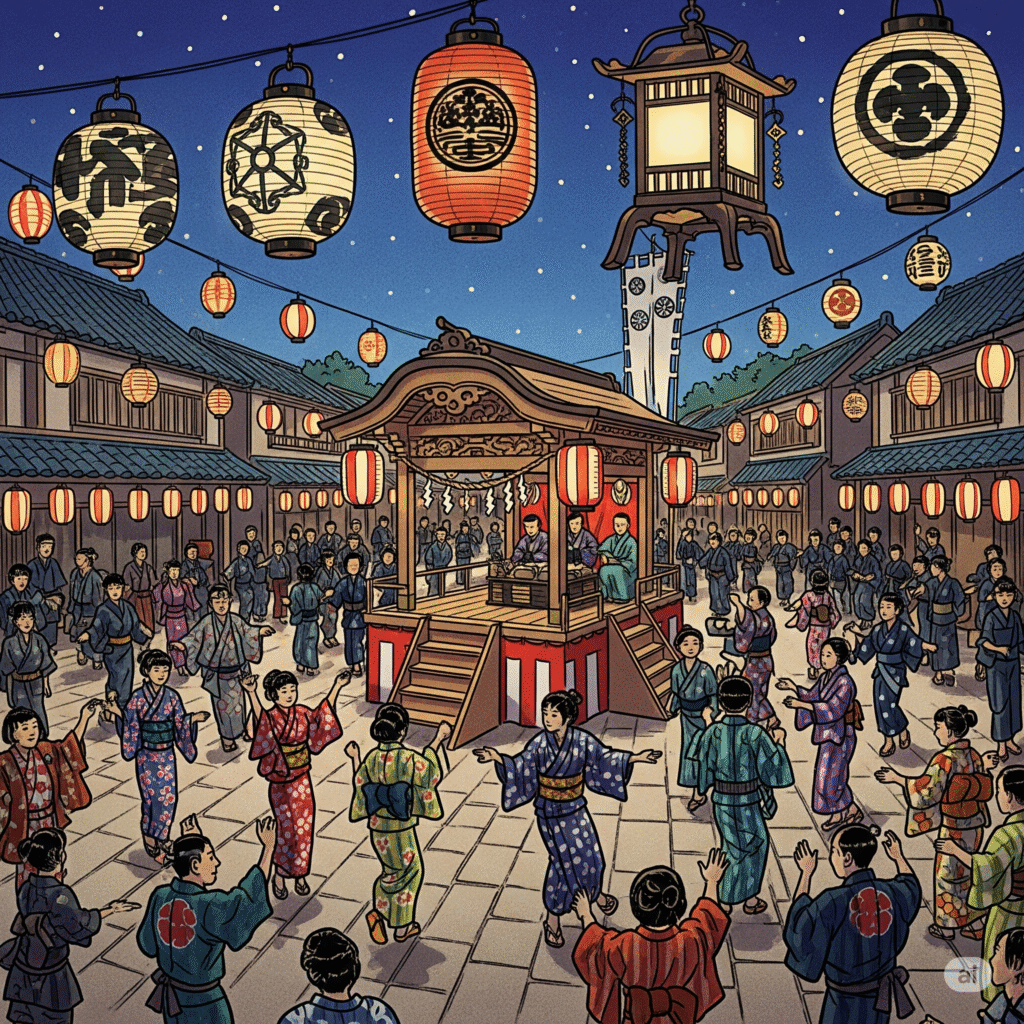

One of the most joyous aspects of Obon is the Bon Odori — a communal folk dance performed in parks, temple grounds, or town squares. People, dressed in yukata (summer kimonos), dance in a circle around a central raised platform called a yagura, often accompanied by live drumming and singing.

Each region has its own Bon Odori style, with unique choreography and music. The dance steps are simple, symbolizing unity and gratitude, allowing everyone to participate — from elders to children. It’s both celebration and remembrance, a way of sharing space with those who are no longer here.

Floating Lanterns: The Farewell

As Obon draws to a close, families bid farewell to the visiting spirits through okuribi — “sending-off fires.” The most poetic version of this is tōrō nagashi, the floating of lanterns down rivers or out to sea. These glowing lights represent the spirits’ journey back to the afterlife, and their gentle drift across water is both beautiful and bittersweet.

One of the most famous lantern ceremonies is held in Hiroshima’s Peace Park, where thousands of lanterns float on the Motoyasu River — honoring not just ancestors, but victims of war and disaster.

A Festival of Family and Memory

Obon is not just about the past — it brings families together in the present. It’s a time for reunions, storytelling, and passing down traditions to younger generations. Despite its solemn undertones, Obon is filled with laughter, fireworks, and shared meals under paper lanterns.

In a world where people are often disconnected from their roots, Obon stands as a gentle reminder: the past is never truly gone — it walks with us, dances beside us, and glows softly in the summer night.